GREASE (1978)

Not exactly The Warriors (see previous entry here: https://talesfromweirdland.tumblr.com/post/157788924410/my-favorite-films-part-1), but it’s still about gangs. I saw Grease in the 1980s, sick at home from school (well). I was about 9. Heck did I know that most of the actors were well past high school age. When you’re 9, even 12 is old. 12 is ancient. 12, that’s one foot in the grave already. You don’t know the difference between 16 or 40. But I loved Grease. Its spirit, its bravura. I was always hoping for someone in my class to suddenly jump on a table to start singing, start belting, with all of us joining in right on cue and doing our little solo parts, but no fairy dust ever landed on my school. My friend jumped on a table once and slipped, he was out for like a month. Grease simply encapsulates a part of my childhood: the sunny and hopeful part, the part where every face is friendly and nobody dies.

LA VERITÉ (THE TRUTH) (1960)

Speaking of reflecting a time, as we seem to be doing, this dark film represents pre-tourist Europe to me, when buildings were black with soot and thick, dusty curtains hid the cracks in the walls. Look at the book that the woman on the right is reading: La femme solitaire. Intellectualism wasn’t a dirty word yet, it was a proud affliction. Elitism was something you’d strive for. Screw the dumb masses and their poor taste, but give them all the liberties they deserve–elitism for the people. That’s 1950s/1960s France, or rather, Paris, where this film takes place.

I’m a fan of Brigitte Bardot. In fact, I think I’ve seen all of her films, even the bad ones. More a natural phenomenon than an actress, she starred in films that mostly were spins on her public persona: reflections on and reactions to the phenomenon. In Vie privée/A Very Private Affair (1962), we see scenes from her mad fame: the constant stalking by paparazzi (a relatively new thing at the time); the hostility from authorities, parents, newspaper editors, moralists (when a man was murdered on a train at Angers, she–who had perverted moral standards!–was held partly responsible); the hysterical world of cinema; the deceptions and betrayals. In Don Juan (1973), she’s a seductive, destructive siren. In En cas de malheur/In Case of Adversity (1958), she is an indifferent prostitute. In every film, in fact in every scene, she has the same expression on her face–her own: a kind of sultry pout. “She doesn’t act,” director Roger Vadim (her first husband) said. “She exists.” That’s not to say she couldn’t act: especially in her later films, when disillusions with fame had given her a kind of world-weary gravity, she holds her own against whoever she is paired with: Marcello Mastroianni, Sean Connery, Michel Piccoli, Jeanne Moreau. La Verité is a shining example of what she was capable of, and also a great film. I love the monochrome interiors (is it ever daylight?), the darkened bistros, the sooty Parisian buildings. It’s a film that starts off dark–and then gets darker. In a rare moment of nostalgia, she herself regarded it as one of the best films she had been in. The first time I watched it, it was without subtitles, and I didn’t really understand what was going on. People would suddenly kiss, or fight; they’d flee, their bags packed; they’d meet up in secret, or so I thought. All that intrigued me, and ever since then the film to me still has this air of vagueness, of mystery. A window into a lost world.

Bardot’s public persona, more than her artistic persona, ran counter with her actual personality. Though seen as the face of sexual liberation, she was a traditionalist who preferred playful eroticism to explicit sex, masculinism to feminism, austerity to extravagance, and who supported De Gaulle at the height of the French civil unrest in May 1968. Her breakthrough film, Et Dieu… créa la femme (1956), made at a time when skin=sin, was a world-wide scandal, and the term “sex kitten” was invented for her–yet she downplayed her own looks and was sooner to agree with her critics, who wrote that she had “the face of a housemaid”. She was never styled, her uncombed, beehive hairdo and cat-like eyeliner were her own casual inventions, she went around barefooted and wore jeans not to shock but because she felt comfortable that way. (A creature of spontaneity, she was the first to glamorize the natural look: there aren’t many photos of her wearing elegant dresses, jewellery, girdles, high heels, etc. In other words, she wasn’t a manipulative vamp.) Unlike, say, Marilyn Monroe, she had never sought fame, and when she became famous, she quickly learned to loathe it. She routinely rejected huge offers to appear in US films. She spoke English the way other people eat with chopsticks. A private person who liked to pluck guitar and brood, she was always followed around, scrutinized, harassed: when she landed in Saint-Tropez in the late 1950s to hide, it promptly became a jet-set hotspot.

Eventually, aged 39, she did something unthinkable in our fame-obsessed society: she resolutely quit acting. She hasn’t been in a film since. Instead, she dedicated herself to animal rights, further enraging people, though of course she has to be admired for it. Today, with the industrialisation of animal cruelty, she’s perhaps more disillusioned than ever, yet she regrets nothing, and thus, in a way, she also is more beautiful than ever. That’s Brigitte Bardot, one of my heroes.

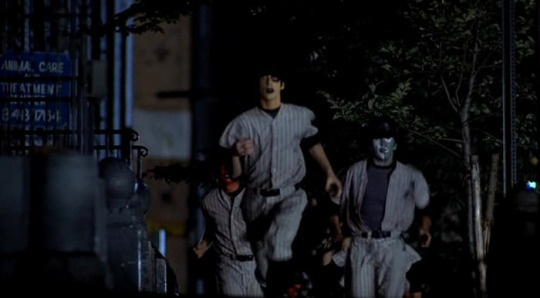

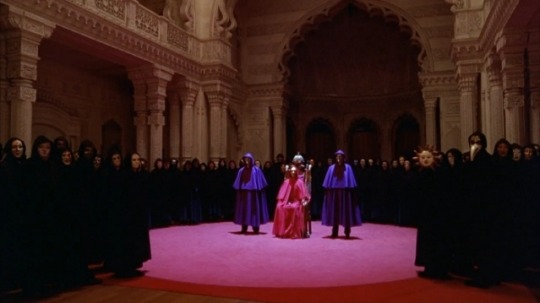

EYES WIDE SHUT (1999)

Seldom did a film connect as strongly with my subconscious mind, my essence, as this one. The sinister Venetian masks, the bizarre rituals, the dark doings that go on in the night, for some reason it all feels very familiar to me. It feels like the natural order of things. I’ve never felt more at home than during the scene from which the above image was taken. (I’m never more myself than when I dream.) I watched it all hypnotized–a deep truth was being shown here. One wrong look and someone in a backroom crosses out your name with a special pencil. An accidental misstep, a forbidden word that you, naively, speak out loud, and you suddenly find yourself set apart, branded. Shadows suddenly move as you approach them, bystanders seem to give you brief but penetrating glances. You never quite grasp what’s going on, if you’re breaking an unspoken rule, but you know you’ve stumbled upon something that you shouldn’t have seen. Eyes Wide Shut kickstarted my admiration of Stanley Kubrick, and my interest in the unseen.

RETURN OF THE JEDI (1983)

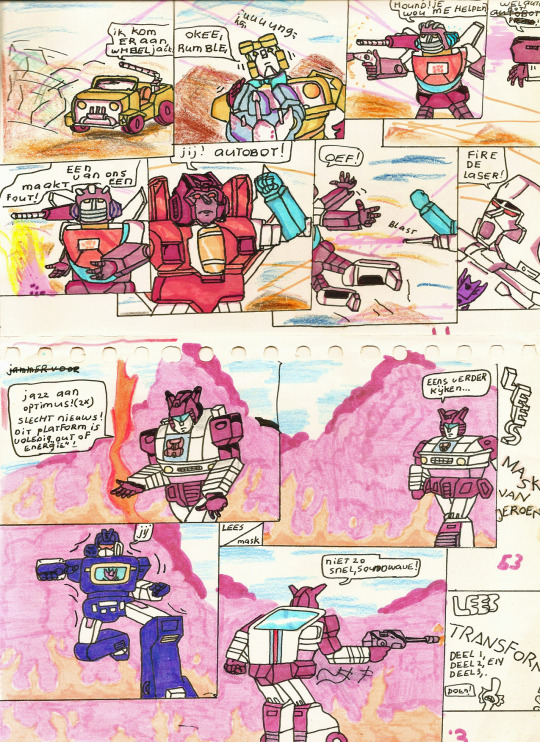

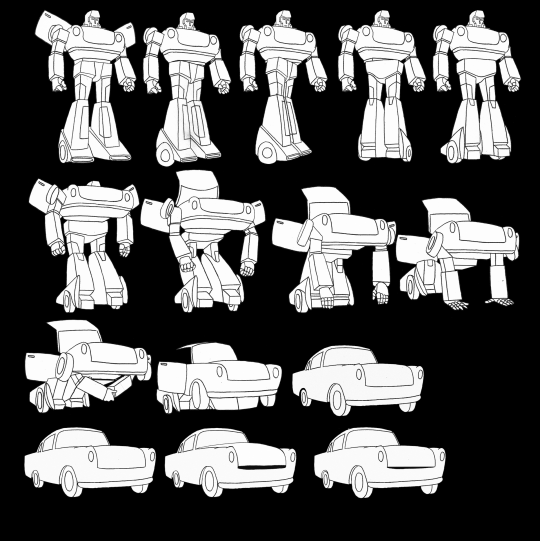

Sure, The Empire Strikes Back is a better film. Granted. But this was the first episode I saw, and it made the biggest impression. There was fantasy–no, there were movies, and there was Star Wars. The franchise wasn’t the peak of the pyramid, it floated slightly above the peak even, it was its own separate entity. And Return of the Jedi, in particular, showed me the fantastical and the grotesque like nothing had ever done. Everything else simply paled in comparison. Jabba the Hutt was my favorite character, but I loved his whole entourage. It was as if someone had designed all those creatures and aliens with me in mind. Right now, for my YouTube animation channel Tales from Weirdland, I’m working on an elaborate, ambitious Star Wars video, a crystallization (of sorts) of my 30-odd years with the franchise. It will probably be the biggest video I’ve made yet. My channel, by the way, can be visited here:

Oh, look at that shameless plug. But it’s my own blog, so I’m allowed. And anyway, I’m proud of my videos. And I fully realize that this text will survive me–that 200 years from now, someone might read this and wonder. My end game would surprise you, esteemed reader.

That said, I should head back to my Star Wars video now and start scene 71 (man). There’s a lot of work to be done still, but hopefully I can upload the finished video around May 2017, 40 years after the first film. (I didn’t plan it to coincide with that actually, never even thought of it, but now that I’m aware of the anniversary I’m trying to get it done by then.)

Next time, I salute you.